Glacier National Park

I’ve been in Montana for a little over six months now, and I’m lucky enough to have watched this place come alive. Looking out at the fields of wildflowers, it’s hard to believe just a few months ago this was all just drifts of snow. The transformation that occurs in this state is remarkable. I’ve been eagerly waiting for the mountains to thaw out since I got here. I remember heading to Glacier in the middle of January to find the place abandoned; even in May the snow was just barely beginning to melt.

A couple weeks ago now, I made the trek back with my roommate and a couple other friends and found myself absolutely stunned. Going-to-the-Sun Road was finally opened, and reaching the heart of the park had become a cinch.

We started a little late the first day, getting out on the trail just after lunch. Our first stop was just before St Mary’s Lake, on the east side of the park. To get there we drove right through the heart of the park. Going-to-the-Sun Road winds its way from West Glacier, across to St Mary. In between, the road snakes past some of the most pristine wilderness in the country.

About an hour later we started our first hike out to Virginia Falls. The forest at the trailhead is currently reeling from the massive Reynold’s Creek Fire, which raged through this part of the park back in 2015. While the skeletons of the former forest remain, the wildflowers that filled the understory dominated the landscape in July. The fireweed was in peak bloom, and blanketed both sides of the trail. About a mile in we crossed St Mary Falls on a wooden bridge, and continued up the side of the St Mary River. It’s been unseasonably hot in Montana this summer, and the sun zeroed in on us like a laser beam. We continued up past the former burn area and made our way into the forest.

After another mile up, I could hear the falls well before we saw them. Virginia Falls cascades magnificently down from spruce-covered cliffs. These are some of the largest falls in the park, and they sure do not disappoint. The icy mist soaked us as we took in our surroundings. It was a much-needed relief from the heat of the day. On our way back, we headed down to the river for an epic view of the falls in their entirety.

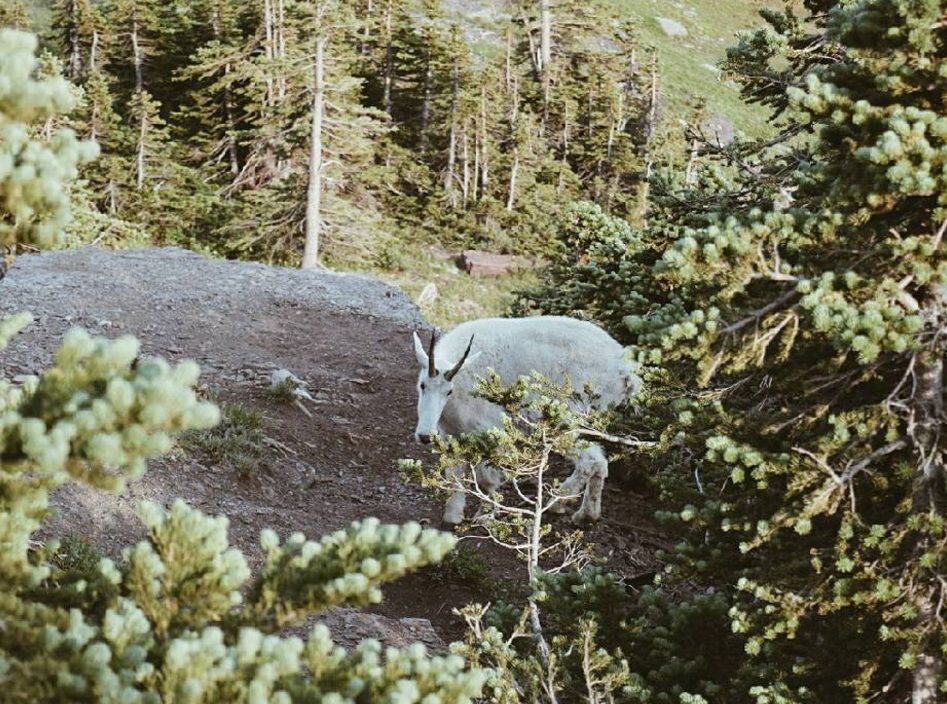

With still plenty of daylight remaining, we were back at the car and discussing our next hike. Behind the visitor’s center at Logan’s Pass (the highest point on Going-to-the-Sun Road), starts the trail up to Hidden Lake. Within seconds of stepping out of the car we were mere inches away from a mountain goat.

We headed up the trail as the sun lowered, and trudged our way across snowfields in the shadow of Clements Mountain. Even in mid-July the snowdrifts made parts of the trail almost impassable. I counted twelve mountain goats by the time we reached the overlook above Hidden Lake (the trail goes further but was closed due to grizzly sightings).

The trip back down was a little trickier. Walking down the side of a mountain on a half-melted snowdrift turned out to be no easy feat. Following the crowd, we all decided the best option was to butt-slide back down the trail. Soggy and sunburned at Logan’s Pass, we were greeted by a few more mountain goats on our way back to camp.

The next morning was an early day. This time we headed north of St Mary, up to the Many Glacier section of the park. With the road ending on beautiful Swiftcurrent Lake, the views in Many Glacier are hard to beat. Here, our trail led us up to the legendary Grinnell Glacier.

It started out easy enough, winding from behind the Many Glacier Hotel and up to Lake Josephine. If you arrive early enough, you can even boat across both lakes (which shaves off half the distance of the hike). The group just before us even spotted a moose on the trail.

After Lake Josephine, the trail forks into an upper and lower section. We opted for the upper section, and started to climb quickly. The next couple of miles were straight uphill, but the views kept us in a state of amazement. We rose hundreds of feet above spectacular Grinnell Lake, whose emerald-colored waters made it easy to spot between the dense woods below.

Mid-July is the peak for alpine wildflower season, and the trailsides going to Grinnell Glacier were spectacular. Beautiful bear grass stood out for miles, with its tall stalks filling entire fields. Somewhere before the fifth mile we reached a sign warning us of a snow hazard. Unfathomed after our sledding at Hidden Lake, we continued and found the snow drifts here much less menacing. We even managed to find a snow free bypass.

The traffic seemed to thin out past the snow banks, but we pushed on. Every group was telling us that we were almost there. The uphill continued (and hadn’t really stopped since we left Lake Josephine), but the wildflowers kept us in awe. Bighorn sheep munched through the fields, as the bear grass transitioned into the alpine zone.

Four-tenths of a mile to the glacier, the sign read. It’d been almost four hours now since we left the trailhead and we were definitely starting to slow down a bit. Meandering through fields of granite boulders, we were finally in sight of our destination. At the top of the cirque we found ourselves face-to-face with the massive Grinnell Glacier, where sky-scraping peaks surrounded us on nearly every side.

Sadly, by 2030 it’s estimated that nearly all of the glaciers within Glacier National Park will have disappeared due to climate change. Grinnell Glacier is a unique chance to come face-to-face with the disappearing features that make this park world-famous. Glacier is incredible, there are no two ways about it. With 95% of the park being untamed wilderness, it’s one of the few areas left in the Lower 48 States where you can truly get off the grid.

To check out more of Nick's adventures, follow him on Instagram.

Contributor

Nick Dorr

Nick Dorr currently works for a non-profit in Northern Montana. He spends most of his free time outdoors.